Ornamental Shrimp: Dentist of the deep now commercially bred

by Ian Vorster

Approaching through the gloomy blue, a diver’s flashlight arcs back and forth as he enters a Caribbean Sea cave. His exhaled bubbles drift up in intermittent bursts like hot air balloons released against an evening sky. Apparently unaware, a banded coral shrimp (Stenopus hispidus) seems to imitate the diver’s deliberate swimming motion as it makes its way across a slab of nearby coral.

Banded coral shrimp live at depths of between 15 and 130 feet in tropical oceans. This minuscule creature has a symbiotic relationship with larger “client” fish, like groupers and moray eels. At locations known as “cleaning stations” on a reef, the shrimp dance from side to side, letting potential clients know they’re open for business. When a visitor stops in, the shrimp eat its external parasites. There are even videos of the shrimp scouring divers’ mouths at the cleaning stations. This behavior earned the little animals names like reef dentist or reef janitor.

The marine aquarium industry commonly trades these reef dentists as an ornamental (an organism, captive or bred for the hobby aquarium industry). And, until now, the majority of shrimp sold commercially for aquariums have been wild-caught, raising concerns about how removing them will affect the reefs they inhabit, and their many finned clients—imagine losing your dentist. While it was known that the shrimps’ cleaning behavior served as a natural method of parasitic disease control, a study published in PLOS One (Militz, Hudson, 2015) found that these dentists of the deep also consume eggs and larvae of a harmful monogenean parasite, Neobenedenia sp., thereby reducing infection of host fish by half compared to controls.

Successful Breeding Benefits Commercial Industry and Shrimp

Cleaner shrimp shave an unusual sexual system, which makes them hard to breed. Individual shrimp initially develop and reproduce as males, and then they develop female reproductive organs, becoming hermaphrodites that function as both males and females throughout the reproductive cycle (Fiedler, 1998). The adults regularly spawn eggs, but efforts to culture them in captivity have largely proved unsuccessful, primarily because the cycle from egg to adult takes on average about six months, during which most of the larvae die.

Funded by Virginia Sea Grant, efforts at Virginia Tech’s Agricultural Research and Extension Center (AREC) at Hampton Roads have resulted in captive breeding of the following ornamental species: the blood fire shrimp (Lysmata debelius), the banded coral shrimp (Stenopus hispidus), the sexy dancer shrimp, (Thor amboinensis), the peppermint shrimp, (Lysmata wurdemanni), and the harlequin shrimp (Hymenocera picta).

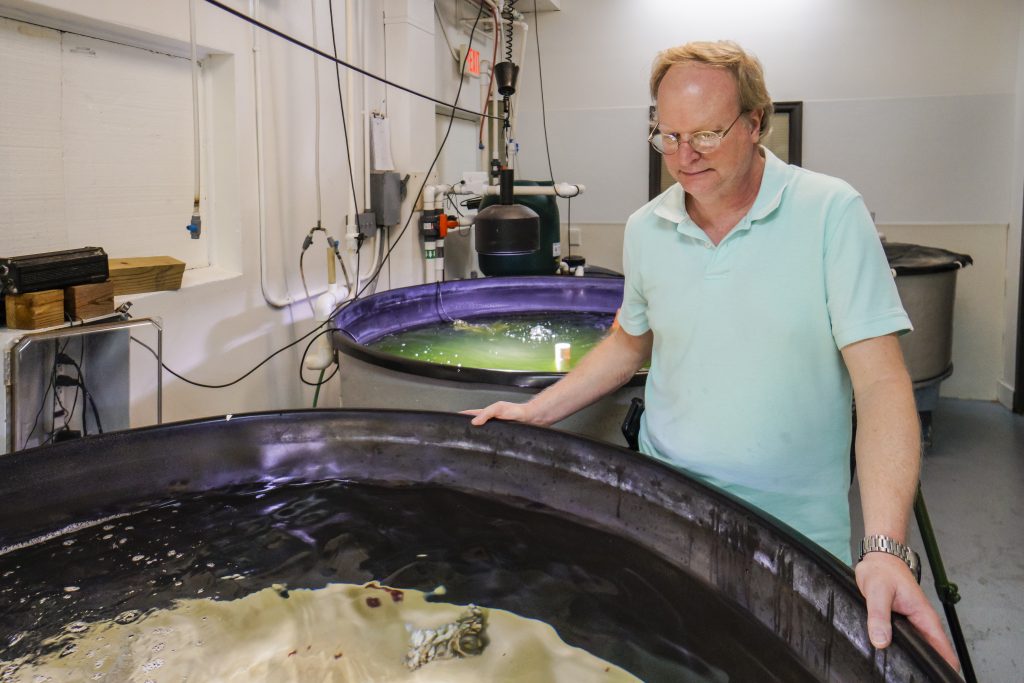

Steve Urick, the lab and research specialist at VSAREC, has successfully led the program. As he decants a small tub of water containing two blood shrimps into a tank he says, “Several universities and scientists have been able to bring these shrimp species through the different life growth stages, but they have never really been bred on a commercial scale.” That is primarily whatVSAREC has been working on—raising them at a commercial level so that a local, newly developing fish farm can breed them and sell them to wholesalers that will then ship them to customers. Among the various benefits for the commercial industry, this effort would also alleviate the pressure of wild harvesting on reefs.

Partnerships, Problems, Protocols, and Procedures

“One of the problems in this process is that shrimp, unlike finfish, take a long time to go through the metamorphic process,” Urick says. “So, if the conditions aren’t perfect a shrimp can mark time—essentially ceasing its development to remain in the current stage of growth for days, and even months.” This compounds the challenges for a commercial hatchery because it means more time, more labor and, consequently, increased costs.

“You need to have all the protocols and procedures in place for the shrimp to move through their different life stages smoothly, and possibly even more quickly,” he says.

To ensure that the shrimp they raise go to market in a reasonable and regular amount of time, VSAREC is experimenting with new live feeds and enriching nutrients to optimize growing conditions. The lab is still refining the production of the live feed, a species of copepod (what shrimp eat)—that can be raised on an inert diet. (Yes, the live feed has to be fed as well.) “It is still unknown how big of a role this particular species will have on aquaculture, but the initial results are promising,” notes Urick.

There are numerous benefits of captive-raised shrimp, perhaps the primary one being that they would be available year-round, whereas wild-caught shrimp are only available during certain months of the year. And breeding shrimp would not only minimize harvest pressure on wild populations but also improve the industry because commercially-bred shrimp also raise better and ship better.

The benefits of applied science are generally reflected by how integrated the research is with industry stakeholders. And that integration is in turn reflected by partnerships—which are a hallmark of all Sea Grant programs. Chris Bentley, the seawater lab manager at the Virginia Institute of Marine Sciences contributing his industry knowledge and commercialization experience to this collaboration. Quality Marine, a primary supplier for the aquarium industry, also provided the broodstock and industry-based guidance for species selection. The success has been a long time coming, and it showcases the capacity of partnerships.

Many species of cleaner shrimp have a symbiotic relationship with larger “client” fish, like groupers and moray eels.

Success with Clown Fish Paved the Way

A few years ago, a fish farming company asked VSAREC for help diversifying their product.

“Looking for some alternate solutions to make the company successful, we applied for and received a grant from Virginia Sea Grant and Virginia Tech to fund a project to breed ornamental finfish commercially,” says Michael Schwarz, AREC Director. This allowed the company to transition from food fish to clownfish. “It’s an emerging marine aquaculture sector with socio-economic development opportunities, and with the initial success we are now looking at launching a second company on a similar route.”

As Virginia Sea Grant, Virginia Tech and the Virginia Institute of Marine Science Eastern Shore Lab collaborate closely on the development of the first ornamental shrimp aquaculture farm in Virginia, the tiny dentists of the deep are free to practice their microabrasion techniques in the cleaning stations of the world’s tropical oceans.

References

Militz, Thane A & Hutson, Kate S. Beyond Symbiosis: Cleaner Shrimp Clean Up in Culture. PLOS, February 23, 2015.

Fiedler, C. Functional, Simultaneous Hermaphroditism in Female-Phase Lysmata amboinensis (Decapoda: Caridea: Hippolytidae) Pacific Science 1998, vol. 52, no. 2: 161-169, University of Hawaii Press.

Takeaways:

• Banded coral shrimp have become known as “reef dentist” to larger client fish, like groupers and moray eels.

• When the client fish and shrimp partner up, the shrimp eat its client’s external parasites.

• Ornamental shrimp are commonly captive or bred for the hobby aquarium industry.

• Mostly wild caught, it raises concerns about how removing the ornamental shrimp will affect the reefs they inhabit, and their many finned clients.

• Virginia Tech’s Agricultural Research and Extension Center (AREC) works on captive breeding of these ornamental species.

• Breeding ornamental shrimp would minimize harvest pressure on wild populations, but also improve the industry.

Published June 12, 2018.

The majority of shrimp sold commercially for aquariums have been wild caught, raising concerns about how removing them will affect the reefs they inhabit, and their many finned clients — imagine losing your dentist.

“It’s an emerging marine aquaculture sector with socio-economic development opportunities, and with the initial success we are now looking at launching a second company on a similar route.” – Michael Schwarz, VSAREC Director