Cedar Island marsh could mean more bird habitat, less erosion for Eastern Shore

Standing along the seaside of Virginia’s Eastern Shore, sandy barrier islands fend off waves, protecting the coastal communities behind them. This protection isn’t guaranteed, though. Extreme storms and sea level rise can weaken the islands, causing them to breach, migrate landward, or drown entirely. This leaves the communities behind the islands more vulnerable to storm surge and erosion, and erases an important coastal habitat.

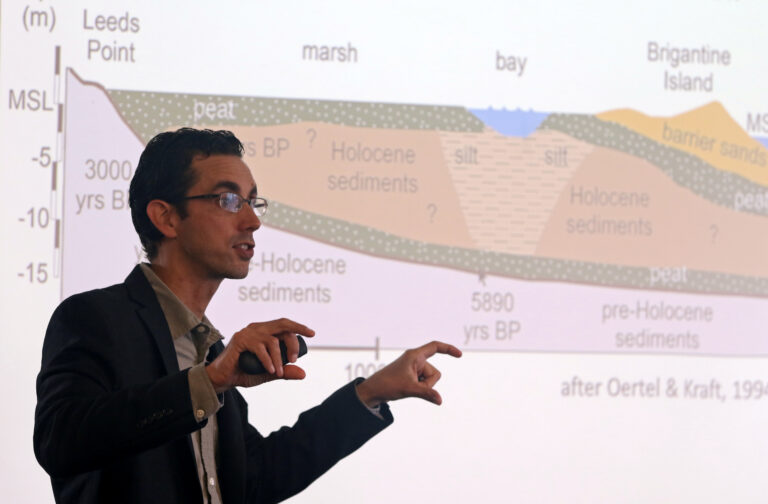

A new design proposed for Cedar Island would stabilize the southern 2 miles of the 10-mile island by creating about 200 acres of marsh behind the barrier island. The design study, supported by a $250,000 National Fish and Wildlife Foundation grant, was led by Virginia Institute of Marine Science Associate Professor Christopher Hein and included experts in coastal geology, ecology, engineering, and policy.

Cedar Island has been moving toward land at an average rate of about 18-20 feet per year since the 1850s, and more recently, the effects of sea level rise and marsh loss behind the island have more than doubled this rate. Most of this migration occurs in sudden spurts, when major storms or tidal inlets on the island push sand from the front of the island toward the back.

Marsh behind the barrier island can slow the migration process by providing a platform for the sand to land on, preventing it from washing away into the bay behind the island. In turn, the island shields the marsh behind it from waves and can provide enough sediment for the marsh to grow. When an island becomes too thin, storms can also create openings in the island known as inlets, where high energy waves can pass through to the bay behind the island. These inlets can hasten the island’s erosion and damage any marsh behind it.

The southern half of Cedar Island is moving landward faster than the northern part of the island, which is already supported by a healthy backbarrier marsh. This marsh provides a platform for sand to land on, and allows the island to build up sand dunes. Without a marsh, any sands washed over from the beach and dunes will disappear into the lagoon, leaving the island lower, narrower, and more sensitive to new inlets.

The proposed project would fill in parts of the lagoon in order to create a backbarrier marsh behind 2.5 miles of the southern part of Cedar Island. The marsh design is based on the coastal processes long-recognized by the scientific community, and with understanding refined by some of Hein’s earlier Sea Grant-funded research on the barrier island system. But, this is the first time these concepts have been put to work to improve coastal resilience.

“This design provides an opportunity for us to see these processes in action, and test how a marsh can help a barrier island,” Hein said. “The overall goal is to improve resilience of the whole system: the marsh and the island itself.”

To inform the marsh designs, a team of scientists and engineers mapped out the channel, lagoon, and existing marsh areas behind southern Cedar Island. They used sediment cores and other measurements of the lagoon to determine where a marsh could be efficiently built. They also looked at the sediment makeup and types of marsh plants at reference sites on the northern end of Cedar Island to model their marsh designs after.

“This design provides an opportunity for us to see these processes in action, and test how a marsh can help a barrier island,” Hein said.

If the Cedar Island marsh proved successful, similar designs could be developed for more populated barrier islands, such as those along the Jersey Shore.

The team also identified nearby sediment deposits in the lagoon that could be “borrowed” to build up a platform for the marsh. Hein said more modeling work would rule out any unintended consequences of taking sand from this part of the system. If additional research continues to show promise, the marsh construction itself could cost several million dollars to complete. Altogether, the project could be permit-ready by 2023, Hein said.

The goal of the project is to slow Cedar Island’s migration and prevent the island from breaching at the site of a former tidal inlet, rather than anchor the island in place permanently. This allows the island to remain in a “natural” state, while still give the island a longer lifespan and extend protection for the coastal town of Wachapreague, which is home to a Coast Guard Station, the VIMS Eastern Shore Lab, and several commercial and charter fishing operations.

If the Cedar Island marsh proved successful, similar designs could be developed for more populated barrier islands, such as those along the Jersey Shore. This nature-based design could enhance the overall marsh-barrier system’s resilience without hardening the shoreline.

“This idea has been recognized in the scientific community for some time, but it’s only now coming into vogue in the management community,” Hein said. “In this case, we don’t stabilize the beach with nourishment or rocking it up. Instead, we help slow its island migration by building up the marsh, and gain all the other benefits that come with that.”

In addition to slowing the island’s migration, the marsh would create additional habitat for birds and serve as a sink for carbon and other nutrients. This nature-based design would help preserve a 2-mile portion of one of the longest stretches of wilderness on the East Coast.

The Nature Conservancy began acquiring barrier islands, including most of Cedar Island, in the 1970s to preserve pristine coastal habitat. Under TNC ownership, the islands have been allowed to migrate and change as they would naturally, according to Jill Bieri, lead scientist at The Nature Conservancy’s Virginia Coast Reserve. Bieri and others provided input throughout the marsh design project proposed for Cedar Island.

“We believe the best way to manage them is in their natural state,” Bieri said. “We certainly understand with climate change effects like sea level rise and more frequent storms, that it’s worth exploring, and we’re supportive of understanding options we might have that will involve some nature-based solutions that may help maintain these islands.”

Takeaways:

- A new design proposed for Cedar Island would stabilize the southern 2 miles of the 10-mile island by creating about 200 acres of marsh behind the barrier island. The goal of the project is to slow Cedar Island’s migration and prevent the island from breaching at the site of a former tidal inlet.

- Cedar Island, a barrier island that provides shoreline protection for the Eastern Shore, has been moving toward land at an average rate of about 18-20 feet per year since the 1850s, and more recently, the effects of sea level rise and marsh loss behind the island have more than doubled this rate.

- If the Cedar Island marsh proved successful, similar designs could be developed for more populated barrier islands, such as those along the Jersey Shore.

Photos by Aileen Devlin | Virginia Sea Grant

Published November 30, 2021.

Hein CJ, Fenster MS, Gedan KB, Tabar JR, Hein EA and DeMunda T (2021) Leveraging the Interdependencies Between Barrier Islands and Backbarrier Saltmarshes to Enhance Resilience to Sea-Level Rise. Front. Mar. Sci. 8:721904. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.721904