Offshore wind offers possibilities for aquaculture, recreation, research

Twenty-seven miles off the coast of Virginia Beach, two wind turbines sit out of view from the shoreline. By 2026, Dominion Energy will add 176 more as part of the Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind project. In addition to the 660,000 homes these turbines could power, a second opportunity exists in the waters between the turbines — colocation.

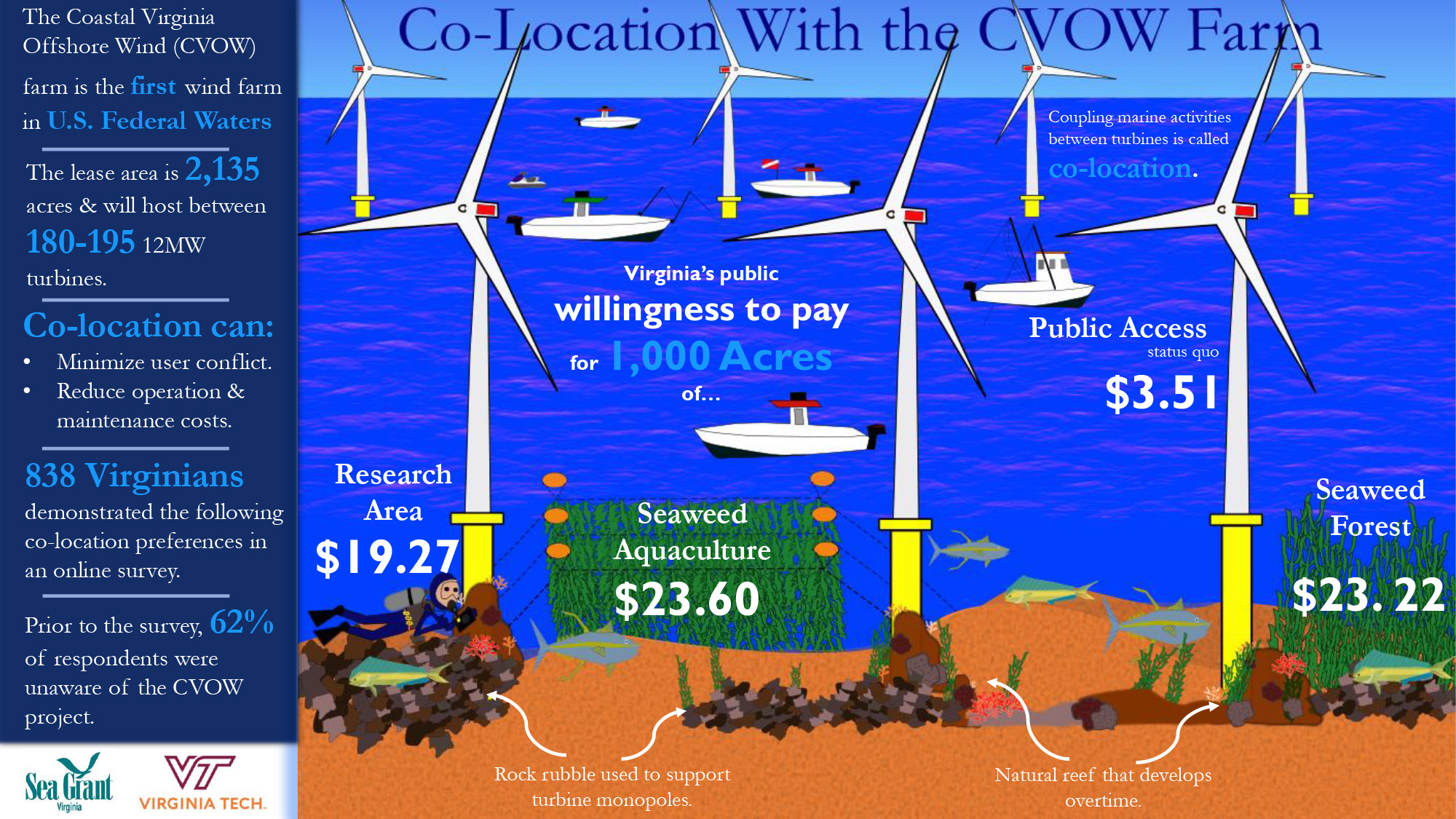

Since the turbines will likely be placed just under a mile apart from one another in the lease, this ocean area could double as a space for other activities, like seaweed aquaculture or research. A recent survey shows public preference about several colocation activities: seaweed aquaculture farming, an unharvested seaweed forest, a designated research area to study the effects of offshore wind, and recreational boat access.

“You’re maximizing that space that’s already destined for human activity,” said Shannon Fluharty, who conducted the survey as part of her master’s research at Virginia Tech. “Especially in Virginia, we have imports and exports, traffic, recreational and commercial fishing, and also the migration patterns of animals in the ocean as well. If you can consolidate some of that into one area of ocean, you can leave some of the other areas open to all those other activities.”

The survey, led by Virginia Sea Grant Aquaculture Graduate Research Fellow Shannon Fluharty and Assistant Director of the Seafood Agricultural Research and Extension Center Jonathan van Senten, is the first to evaluate public preference about combining offshore wind and aquaculture in Virginia.

In each survey question, respondents from across Virginia were presented with three choices: two different options for colocation activities, each associated with an annual tax, and a third option for the status quo — public access — with no annual tax. Each of the 838 survey takers responded to four questions with different options, for a total of 3,352 votes for different colocation scenarios. The survey used an annual tax as a way to assign a dollar value to public preference for combining other activities with offshore wind.

The combination valued highest by respondents was a four-way split of the lease area, with a quarter of the area designated for recreation, a quarter for seaweed aquaculture, a quarter for a seaweed forest, and a quarter of the lease as a research area, which was associated with a $39 annual tax.

“What our results told us was that the public was interested in colocation, and they were interested in all the colocation activities,” Fluharty said. “Regulators or the offshore wind industry might have some support if they were to pursue colocation in Virginia.”

In scenarios where the entire lease area was used for a single colocation activity, seaweed aquaculture was valued highest with an associated tax of $23.60, followed by $23.22 for a non-harvested seaweed forest, $19.27 for a research area, and $3.51 for public access. Although colocation would not necessarily require a tax to occur, the hypothetical taxes in the survey allowed respondents to put a dollar value on the benefit they perceived from colocation.

“Usually when you’re trying to value things like the environment, that’s very difficult to do. It’s not a market good, so you have to do that through an indirect method,” van Senten said. “It allows us to say, ‘OK, these people clearly value having something that’s sustainable as an option — How much do they value it?”

“What our results told us was that the public was interested in colocation, and they were interested in all the colocation activities,” Fluharty said.

Combining activities like aquaculture, research, or a seaweed forest in the leased area would also allow businesses to share operational and maintenance costs. Before conducting the survey, Fluharty estimated how much it would cost to implement and maintain any of the colocation activities. She found that each of them would cost less than $1 annually for a 1,000-acre area.

Exploring colocation at the onset of this project, the first offshore wind farm in federal waters, could make it easier to combine aquaculture and offshore wind in the future — both of which can require permits and can be controversial, according to Fluharty. The four colocation activities included in the survey were all identified as compatible with Dominion Energy’s lease area based on a focus group Fluharty conducted with professionals in industries related to offshore wind.

“It might make the transition more smooth if we’re thinking about all the opportunities that are associated with the new industry from the beginning,” Fluharty said.

Given that offshore aquaculture can generate public controversy, van Senten said he was surprised by public willingness to pay for seaweed aquaculture. Although survey respondents weren’t asked to provide a reason for their choice, van Senten said that during the focus groups, participants seemed to recognize the economic value provided by the aquaculture.

“They both provide habitat, they both provide carbon uptake, but you could eat the seaweed from the aquaculture farm. It employs people,” van Senten said.

While the results of this survey are only applicable to public opinion on the Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind Project, the survey and analysis from this research could be adapted for other offshore wind projects.

“With so many different projects that are being sited and developed and talked about all along the coast, you’re going to have these user conflict issues everywhere,” van Senten said. “I think Shannon’s study could be used as a roadmap to look at other wind farm projects, and to ask similar questions.”

Takeaways:

- Combining activities like aquaculture or research in an offshore lease area, or colocation, can reduce user conflict and help businesses share costs.

- A survey, led by a Virginia Sea Grant Graduate Research Fellow and an extension agent, is the first to evaluate public preference about combining offshore wind and aquaculture in Virginia.

- Survey results indicated a public interest for colocation of aquaculture, unharvested seaweed forests, and recreational boating in the offshore lease area.

Turbine photo by Lyfted Media on Behalf of Dominion Energy, additional photo provided by Dominion Energy

Infographic by Shannon Fluharty | Virginia Tech

Video by Aileen Devlin | Virginia Sea Grant

Story by Madeleine Jepsen | Virginia Sea Grant

Published Jan. 21, 2022.

“I think Shannon’s study could be used as a roadmap to look at other wind farm projects, and to ask similar questions,” van Senten said.