Fish Forensics: High-tech tracking helps herring return to historic spawning grounds

Cars drive over bridges and roads each day in Northern Virginia, but in the water underneath, there’s a different kind of commute. Each spring marks a spawning rush hour for the fish using these culverts and water connections to travel up and down rivers. These passages can take many forms — anything from small metal tubes, cement culverts, or even wider areas underneath a bridge.

“You’ve probably seen them a lot and don’t really realize that’s what they are,” said Samantha Alexander, a George Mason University alumna who studied fish passages in Potomac River tributaries during her master’s research.

These fish passages allow fish living in the streams to travel for food and habitat throughout the year. In the spring, these passages serve as connection points for alewife and blueback herring, which travel from the Atlantic Ocean to their spawning grounds in freshwater streams all along the East Coast.

Alewife and blueback herring, grouped together as river herring because of their similarities, supported one of the oldest and most valuable fisheries in Virginia, up until the 1980s. Over time, their populations declined — in part due to the dams, roads, and other obstacles that blocked access to the streams where they spawn. The National Marine Fisheries Service listed river herring as a species of concern in 2006, and in 2011, Virginia joined several other states in banning all fishing for river herring.

In 2015, the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement between Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Washington D.C., and the Environmental Protection Agency set a goal to create an additional 1,000 miles of stream access by 2025 — either by removing or modifying dams, or by improving fish passages in disrepair, in order to support migrating fish.

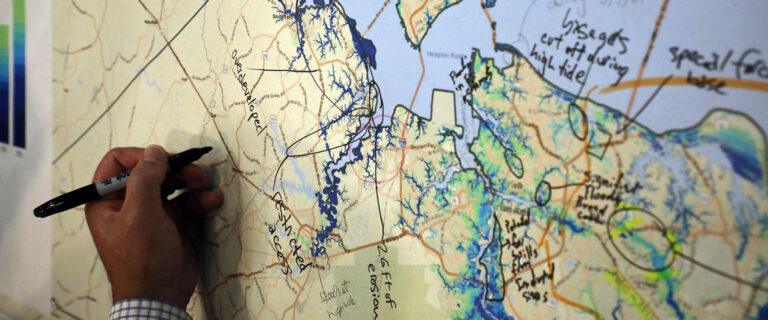

To help support river herring recovery, researchers at The Nature Conservancy developed a mapping tool for fish passages and stream blockages throughout Virginia. While the map identified only dams at first, it expanded to include other structures like fish passages at road crossings, and rated their effectiveness in allowing fish to migrate uninterrupted.

Using the mapping tool, Alexander identified 11 tributaries off the Potomac River that could be important for river herring, and 22 fish passages along those streams that herring would need to cross during their migration. Similar to the techniques used in crime scene forensics, Alexander collected environmental DNA — trace amounts of genetic material that are left behind in the water after a fish swims through — to determine whether river herring were present and using the passages.

Environmental DNA can complement traditional fish sampling methods like netting or electrofishing, according to Alan Weaver, the fish passage coordinator for the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources.

“One of the pitfalls of traditional sampling is that you could sample the same road crossing every week for a whole spring, and within a two-day window, you may have missed the herring run,” Weaver said. “You run the risk of missing that with that traditional sampling. With eDNA, if you get a water sample a few days after the fish have been there, you might still get that positive herring hit.”

With thousands of miles of Virginia streams and many fish passages, environmental DNA can also be an efficient way for researchers to narrow down areas for traditional fish sampling methods.

“There was also a lot of debris accumulation that might prevent fish from moving through an otherwise successful passage,” Alexander said.

Alexander confirmed the presence of river herring at 15 passages along nine of the 11 creeks she sampled. She found that each of the creeks had at least one fish passage the river herring had used successfully.

During April and May of 2018 and 2019, Alexander took water samples when river herring would be using the fish passages to migrate inland. For her research, she sampled near 10 bridges, 12 culverts of varied widths and shapes, three smaller weir-style dams, and a taller dam.

She collected water on both sides of each fish passage to analyze for river herring DNA. If both samples contained herring DNA, then the herring were able to use the passage. If the sample above the fish passage lacked herring DNA, then the herring were blocked and unable to continue upstream.

Alexander confirmed the presence of river herring at 15 passages along nine of the 11 creeks she sampled. She found that each of the creeks had at least one fish passage the river herring had used successfully, and the conditions she found at fish passages generally supported the rankings of different locations in the TNC fish passage restoration tool.

“We saw a lot of passage through significant barriers in the sites lower in the creeks,” Alexander said. “There was also a lot of debris accumulation that might prevent fish from moving through an otherwise successful passage.”

Understanding where the river herring are migrating — and which types of fish passages are easiest for them to cross — will help state agencies with limited amounts of funding prioritize future restoration of fish passages.

“You can’t necessarily sample everywhere, but if you can get evidence that your target fish was there from eDNA, then it directs your next steps,” Weaver said. “It either directs more targeted research, or if you have a very positive result, you can even say, ‘Hey, we’ve got this. This is an area where we need to open up fish passage,’ or it can confirm a fish passage is working.”

Takeaways:

- Fish passages like culverts and bridges help fish like river herring migrate from the coast to fresh water further inland.

- Samantha Alexander collected environmental DNA — trace amounts of genetic material that are left behind in the water after a fish swims through — to determine whether river herring were present near 22 fish passages near the Potomac River.

- She confirmed the presence of river herring at 15 passages along nine of the 11 creeks she sampled.

- Understanding where the river herring are migrating will help state agencies with limited amounts of funding prioritize future restoration of fish passages.

Photos and video by Aileen Devlin | Virginia Sea Grant

Story by Madeleine Jepsen | Virginia Sea Grant

Published January 27, 2022.

“That’s a wide range of temperatures and salinities. It’s interesting to see one species living in such a broad environment,” Nelson said.